USS HOUSTON CA 30

“The galloping Ghost of the Java Coast”

Charles Leslie Lynch

An Early World War II Casualty

By Audie J. Lynch, EdD

In the early hours of March 1, 1942, Charles Leslie Lynch, Gunners Mate Second Class, a

native of Scotland, Arkansas,

lost his life when the U.S.S. Houston, CA30 was sunk in the Battle of the Java Sea. So far as

this writer has been able to determine, Lynch was the first serviceman from Van Buren County to be killed in action in World War II.

Lynch was born January 7, 1919, five miles southwest of Scotland in Liberty Township, a son of Elvin Warner and Maye

Stroud Lynch. He attended elementary

school at Suggs and high school at Scotland, having completed one year at the Clinton Vocational

School. In January, 1937, having completed the

required number of units for high school completion and having reached his

eighteenth birthday, he enlisted in the United States Navy and was sent to the

Naval Training Station at San Diego, California for "boot camp" or

basic training.

Upon completion of basic training,

Lynch was selected to attend an electrical ordnance school in San Diego. When he

completed this school he was assigned to the U.S.S. Mississippi, BB41

where he served until April 26, 1940, when he applied for and was transferred to the Houston. This ship was being deployed to the Far East for a two-year tour and to serve as the flagship of naval forces in

that area. Lynch had requested this transfer because of his interest in serving

in and seeing this part of the world.

At the time Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Charles

had attained the rating of Gunners Mate Second Class and was a gun captain on a

five-inch gun. This was primarily an

anti-aircraft gun, but it could also be used in surface action. Due to a difference in time zones, the Houston became involved in the war in the early hours of December 8, 1941. At that time

the Houston lay at

anchor in the harbor of Iloilo

on Panay Island in the Philippines. The Houston was ordered to get underway and two hours later Iloilo was heavily bombed and the Japanese reported that the

Houston had been sunk.

Such was not the case as the Houston had not been touched.

On several occasions thereafter, the Japanese claimed the Houston was sunk and she was given the nickname

"Galloping Ghost." In a letter

to his parents dated January 2, 1942, Lynch wrote, "Don't worry about the news

reports as to the progress of this war.

The Japs have reported us as sunk two or three times and that's a long

ways from the truth."

For the next three weeks the Houston escorted fleet units out of dangerous Philippine

waters by way of Borneo and Java. Then

she was ordered to Darwin, Australia where she escorted merchant ships carrying men and

supplies to the beleaguered Allies.

During February 1942, she was attacked several times by waves of carrier

based dive-bombers and land based twin-engine bombers. After most of these attacks the Japanese

would declare that the Houston had been sunk.

Actually, the Houston shot down several of the Japanese planes. In one of the last attacks she received

serious damage when a 500 pound bomb hit and destroyed the after gun turret and

killed 48 Houston men and badly wounded more than twenty.

After a hard fought battle with a

Japanese fleet on February 27, 1942, and with the crews almost completely exhausted from

constant battle, the Houston and the Australian light cruiser HMAS

Perth managed to escape the overwhelming Japanese forces. They entered the port for Batavia, Java the afternoon of February 28, 1942, and refueled.

It was then decided that they would attempt a dash through Sunda Strait to safety in the Indian Ocean. All was going

well until at 11:15 P.M. they were approaching the strait separating Java and

Sumatra where they met a Japanese force of ten destroyers and a light cruiser,

which were protecting 60 transports unloading men and materials of war for the

capture of Java. The Houston and the Perth opened fire and the battle to the death began. Other Japanese warships soon joined the

battle.

The battle was a fierce one and the

Houston and the Perth gave it all

they had. At five minutes past midnight the Perth was out of ammunition and sinking. She went under at 12:20 A.M., March 1, 1942, losing more than half her crew. The Houston continued the fight until she was out of

ammunition. At this time she had holes

from numerous torpedoes and fires raged uncontrolled throughout the ship. The Houston sank beneath the Java Sea before 1:00 A.M. leaving more than half her crew dead.

The Japanese captured 368 men from the Houston and 76 of

these died in prison camps. One hundred

fifty men who were reported as having been seen in the water after the ship

sank were never seen again. Lynch was in

the latter group. Approximately 800 men had

lost their lives.

The Navy Department notified Charles'

parents by telegram on March 16, 1942, that he was missing.

This was his status until December 28, 1945, when after prisoners from the Houston had been repatriated and the navy had debriefed them

that Charles was declared dead. The

letter to his parents came from James Forrestal,

Secretary of the Navy. It is not known

how he died.

He,

along with 149 other men, was seen in the water after the Houston sank, but

these men were never heard from again.

Survivors did report that the Japanese engaged in some machine gun

strafing, but no one can be sure of how these men died.

In spite of the loss of this great

ship and two-thirds of her crew, the Houston along with the Perth had given an excellent account of themselves. American, Dutch, and Australian survivors

captured at different places along the Java coast reported the following

Japanese ships as being sunk or grounded:

two cruisers, four destroyers, one seaplane tender, three motor torpedo

boats, three large merchant ships, and three large transports. In addition, several ships were reported as

damaged. The Houston had gone down, gallantly fighting to the last against

overwhelming odds. President Roosevelt

awarded the ship the PRESIDENTIAL UNIT CITATION for her outstanding

performance. For his part, Lynch

was awarded the PURPLE HEART and the BRONZE STAR MEDAL and other medals

posthumously. These medals were sent to

his parents after he was declared dead.

The citation for the BRONZE STAR MEDAL was as follows:

For heroic achievement as a Gun Captain in

the Secondary

Battery of the U.S.S. Houston in action against units of the

Japanese Fleet in the vicinity of Java, Netherlands East Indies

on

February 28-March 1, 1942. Although his

ship had been

badly

damaged by enemy gunfire and the order to abandon

ship

had been given, LYNCH courageously went to his

station

while the ship was losing headway and, despite terrific

heat,

steam and unrelenting gunfire, opened fire on a Japanese

destroyer

on the starboard beam. Remaining at his

gun until

the

HOUSTON began to capsize, he aided greatly in preventing

the

enemy from closing to point-blank range.

His unwavering

devotion

to duty was in keeping with the highest traditions of

the

United States Naval Service.

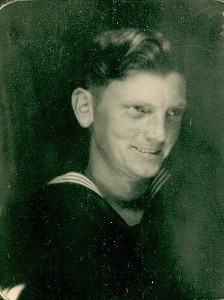

The picture accompanying this

article shows Charles in his Navy uniform surrounded by his medals which were

sent to his parents after World War II had ended.

.

![]()

![]()