![]()

![]()

USS HOUSTON CA 30

“The galloping Ghost of

the

Ralph Edgar Morris

by

Marlene

Morris McCain

(Daughter of R. Edgar Morris)

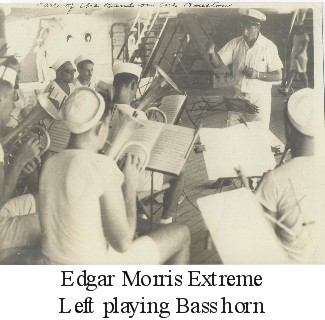

I grew up knowing that my father had always loved

music, and had served aboard USS Houston

during World War II. But like many of our dads, he didn’t talk at all to his

children about the months of battles and the years of mistreatment and

near-starvation in the POW labor camps. His

name was R. Edgar Morris—Eddie to those who knew him well. He always loved

music and he played trombone and baritone and piano. He enlisted in the US Navy

in December 1939, and became a member of USS Houston’s band at age 20. All he

really wanted was to see the world – and play his trombone.

As adults, we recently discovered much information

about my dad, about the Houston, and

her band, which we discovered just recently in some letters Edgar wrote home.

They had been stored in a small box which we’ve begun to describe as our

family’s “Treasure box” since we first opened it…

Becoming

a US Navy Musician...

Even as early as his time in boot camp at Great

Lakes NTS, Edgar Morris would check on the qualifications needed to become a

Navy Musician. Eventually, in San Diego, he took the required examinations and

qualified for Fleet Music School, which only admitted 50 students at a time. He

felt very lucky to get in. “The Navy trade schools,” he said, “rank just below

Annapolis in rating and are better than almost any college… This is paradise to

me; I have all day with music.”

After

graduation Edgar served in Hawaii on USS Northampton

for almost 6 months and loved his work with the band there. In early January

1941, he applied for transfer to the Far East.

In a letter to his folks, he said, “The Navy has gotten into my blood; I

am thinking of making it my permanent home.

I really enjoy riding the waves and am never seasick… I guess you didn’t

know that I turned down an appointment to the Naval Academy while I was in San

Diego; I just want to be a regular sailor.”

After

graduation Edgar served in Hawaii on USS Northampton

for almost 6 months and loved his work with the band there. In early January

1941, he applied for transfer to the Far East.

In a letter to his folks, he said, “The Navy has gotten into my blood; I

am thinking of making it my permanent home.

I really enjoy riding the waves and am never seasick… I guess you didn’t

know that I turned down an appointment to the Naval Academy while I was in San

Diego; I just want to be a regular sailor.”

Besides Edgar, there were four other musicians

aboard USS Nitro, which took 19 days

to transport them to Manila, and true to character, they “got together a little

orchestra and played each night before movies.”

He wrote to his parents, “I am not certain that I shall be sent to the Houston, but I understand that the

bandmaster on the Houston is in

charge of all the bands in the Asiatic station; so maybe I will stay on her.”

Edgar and four other musicians arrived in Manila on

the 29th. Edgar wrote, “The bandmaster told my friend, (“Hap”)

Kelley, and me that we would probably get initiated into the orchestra on

Sunday at the Army/Navy Club when it opens for the first time…I had expected to

be playing the baritone rather than the trombone and was afraid of being transferred

to the USS Black Hawk; but I was

asked to sit in and play piano with the Houston’s

orchestra. I guess I did OK because I am

going to stay on the Houston for

sure!”

There were 19 in the Houston’s band, and 12 or 13 were used for the orchestra. The members of the band were mostly young

fellows, and Edgar had gotten well acquainted with them. One, WALTER SCHNECK, was a friend that he had

known in San Diego. He says they were

considered to be the best band their side of the 180th

meridian! He was proud to be in the

organization and enjoyed his work much more than he had in Honolulu.

“Today, the band played concert at noon,” Edgar

wrote… “I was put on the peck horn (alto horn) and did OK; I would rather play anything

on the Houston than get to play what

I asked for on any other ship. At least

I will get to be in the orchestra playing piano – which I love – and we play

ashore about 2 or 3 times a week.”

On April 17, 1941, the band played about two hours

up on the forecastle for the Admiral and his luncheon party. The next day they

played at the Manila Club for a group of performers from a Russian Dancers

group.

Each evening the orchestra would play before movies

and each noon the band played a few marches and one or two classics up on the

quarterdeck. Edgar was getting along

fine with the unfamiliar peck horn (like a small version of a baritone); the

band played quite a few heavy classics and light operas and most of those

pieces had a peck horn solo or two. He said that their outfit was good

and they could get over the hard stuff pretty easily – and they played a lot of

it!

While the Houston

went out to sea for battle practice and maneuvers, Edgar didn’t get any

practice on the piano because there was not a piano aboard. But he had a

typewriter and frequently typed his letters home and that kept his fingers

pretty limber.

His battle station in the daytime was the machine

gun nest on top of the after mast, and at night he was a pointer for Number Two

giant searchlight on the searchlight platform.

Some of the others of the band were on the 5-inch guns and others did

the handling of the big 5-inch shells on the loading machines.

During the week around July 4, 1941, they were back

in Manila, and it was a very busy week for the band. Every morning was spent in 4th of

July parade rehearsal, but when the 4th arrived, bad weather kept

the boats from going ashore and they missed the parade.

Later that night the weather calmed enough and they

played at the officers club at the Cavite Naval Yard until the wee hours of the

morning. The next night they played at

the Manila Polo Club – such a grand affair that they did not play in their

uniforms, but wore their special shirts, ties and sashes. They started playing

at 8:00 pm and played straight through until nearly 4:30 am. And the next

morning the band played for church!

Edgar wrote his parents on July 11th,

“The choir for church has not been getting along so well with the band and

there was no piano. So on Monday, July 7th, Chaplain Rentz asked me if I thought I would be able to play an

organ if he got me one (and) I told him I would do my best. Tuesday morning, he sent for me and as soon

as I entered his cabin I saw the organ, a small portable one. He told me to try it and he liked it. He then asked me to have a few numbers ready

to play that afternoon. Later, when he

sent for me again, we went up to Captain Oldendorf’s

cabin to demonstrate the organ. The

Captain liked it also; and then the Chaplain gave me a list of numbers to

practice for Sunday in church. Yesterday we had choir rehearsal and it went off

fine. I will be playing church from now

on; I am really happy to have the organ to play because I can keep my fingers

in shape.”

By Sunday, July 13th, the Houston was at Palawan and Edgar played

the organ in church. The service went off very well. Edgar started playing the portable organ on

Saturday night for the singing of a few of the old-time songs before movies. On Sunday, July 20th, now at Tawitawi, after finishing a church service on the Houston, Edgar played the portable organ

on USS Marblehead.

With War

Approaching...

The Houston was

mostly out to sea for battle practice and maneuvers in August and September

1941, there was no mail, and Edgar was unable to write home.

On October 2nd, Edgar was finally able

to correspond again and he reported that “We have been out to sea almost

constantly. These last months have been really hard on morale; we have not had

any liberty and are literally cooped up on the ship. Everyone gets pretty grumpy… Since I last

wrote to you, we have a new bandmaster [i.e.: George L. Galyean,

Bmstr (PA)] and about five new men in the band.”

About three weeks later the Houston was back at

Cavite Navy Yard. In a letter written on November 15, 1941, Edgar wrote, “The

band has really been taking it easy since coming into Cavite two weeks

ago. We play Morning Colors, rehearse a

few hours, then Noon Concert and we are finished until 8:00 the next

morning. I am in fine health and still

like everything and look forward immensely to coming home.” This was the last letter his parents

received. Edgar had had 12 days leave after boot camp in early 1940, but had

not been home on leave since. It would

be almost 4 more years before he would see Illinois again.

The

Battle of Sunda Strait & POW Captivity

As USS

Houston fought her last battle near Bantam Bay on the night of February 28, 1942, Edgar’s battle station was on

the 1.1 pom-pom gun located on the port side next to the forward mast.

After Abandon Ship was ordered, Edgar spent about

11 hours in the water when he was picked up by a whaleboat from a Japanese

tanker. He and seven other Americans

were taken aboard the tanker, which was torpedoed, and run aground. The

Americans were then transferred to an IJN destroyer where they joined about 70

captured sailors from HMAS Perth. From

there they were moved to a large troopship for 9 days, then on March 10, 1942

they were taken by truck to Serang Theater Prison

Camp. On April 15th, they

were moved to Bicycle Prison Camp in Batavia, Java.

On October 11, 1942, Edgar and some others were

transported by “hellship” to Changi

Prison Camp in Singapore, Malaya, arriving on Oct. 16th. Edgar was

separated from the rest of the Houston survivors at this point. Only 12 Houston

men including 2 Marines were ever interned for most of the Pacific War at Changi prison, including my father and one other band

member, Albert M. “Hap” Kelley, Mus1/c, who in March 1941 had made the trip

from Hawaii with Edgar and had gone aboard the Houston at the same time.

On 5 April 1943 Edgar was transferred to Kanchaniburi, Thailand where he worked at “Motor Camp” on

the trucks that supplied the forced labor POW camps further upcountry along the

Burma-Thailand Railroad. After eight months at Kanchaniburi,

Edgar was returned to Singapore—first to Sime Road

Prison Camp, and then in April 1944, back to Changi

where he remained until he was liberated on September 7, 1945. He was flown to

the military hospital in Calcutta, India, by the American ATC – one of the

first of any nationality to leave Singapore.

Very weakened from recurring attacks of malaria—12 attacks in 7

months—Edgar weighed only 100 pounds and was almost totally blind from

malnutrition. Liberation seemed a dream; and he was afraid he would wake up and

still be in Changi.

Kept in Calcutta for more than 2 weeks, Edgar was finally headed home by

Sept. 20th.

Edgar had written about 30 cards and letter-forms

during the time he was a POW, but his parents eventually received just one

postcard in January 1945—the only one they ever got; but, it was enough; they

knew that their son was alive. Edgar had worried constantly because he had

received no replies from his parents to his POW camp correspondence; he feared

that something had happened to them while he had been gone.

By early October 1945 Edgar was back in New York at

the Naval Hospital in St. Albans and could correspond easily with his

parents. He learned that some of the

girls from his high school class had visited his mother in the months and years

after the ship was reported lost; one of them was my mother. They had been friends in high school, but not

sweethearts. He wrote her, asking if he

could come and thank her for her kindness.

On October 8th, Edgar was at last on a

train and headed for Illinois. We found

the stub of his ticket in its original envelope among the things in our

“treasure box.”

On October 11th, he went to see a young

woman who would become my mother. 17 days later they were married! They had

been friends in high school, but not sweethearts. Edgar had

learned

that she had visited his mother in the months and years after the ship was

reported lost. He didn’t go to the Navy Day Celebration; being home was too

fresh and too wonderful – and besides, he was busy getting married! Edgar was restless, and unable to find a

house of their own due to postwar housing shortages, they traveled for the

first several weeks of their marriage.

His dad had offered a job in his own workplace, but Edgar told him,

“I’ve just been ‘locked up’ for 3½ years; I don’t think I can stand to be

inside a building all the time.” He

eventually joined my mother’s family in farming – and he loved it! When he had proposed to her, he told her that

the Navy doctors had said they thought they could promise him 15 years more of

life, but were uncertain about more than that because of his ongoing health

problems from the years as a POW. She

said “yes” anyway – and they were married for 47 happy years before his death

Jan.1, 1993. I will always think that

the good farm cooking, lots of fresh country air, and their happiness

contributed to his much longer life. At

the time of his passing, he was the last of the surviving band members from the

Houston.

learned

that she had visited his mother in the months and years after the ship was

reported lost. He didn’t go to the Navy Day Celebration; being home was too

fresh and too wonderful – and besides, he was busy getting married! Edgar was restless, and unable to find a

house of their own due to postwar housing shortages, they traveled for the

first several weeks of their marriage.

His dad had offered a job in his own workplace, but Edgar told him,

“I’ve just been ‘locked up’ for 3½ years; I don’t think I can stand to be

inside a building all the time.” He

eventually joined my mother’s family in farming – and he loved it! When he had proposed to her, he told her that

the Navy doctors had said they thought they could promise him 15 years more of

life, but were uncertain about more than that because of his ongoing health

problems from the years as a POW. She

said “yes” anyway – and they were married for 47 happy years before his death

Jan.1, 1993. I will always think that

the good farm cooking, lots of fresh country air, and their happiness

contributed to his much longer life. At

the time of his passing, he was the last of the surviving band members from the

Houston.

Edgar never went to any of the USS Houston

Reunions, but he received the newsletter and always read it from cover to

cover. Since he had been separated from

most of the other Houston survivors during the long years in prison camp

perhaps he felt somewhat disconnected.

He continued to correspond with his Australian and English friends, and

in 1954 the English friend immigrated to the United States with his wife and

two small sons, sponsored by Edgar’s dad.

They settled in Illinois, and remained close friends for the rest of

their lives. We saw them often; and when

we visited, my dad and his friend would get off by themselves and talk a mile a

minute for all of the time they had together.

This seemed to be the “support group” that each of them needed.

For Father’s Day, 1990 my husband found another

book for my dad – this one, American Cruisers of World War II, a Pictorial

Encyclopedia. As with any book

relating to his time in the Navy, my dad “devoured” it. He made notations by each ship that he had been

on – even if it was just for church duty.

By the piece on USS Houston CA-30,

he wrote, “My Ship – March 1941 – Sunk March 1, 1942.” That notation is very possessive; he loved

the Navy – and he loved the Houston! He

was so proud to have served aboard her.

Marlene Morris McCain

(Daughter of R. Edgar Morris)

a 'country boy

who was glad to get home'

By Julene Shaffner

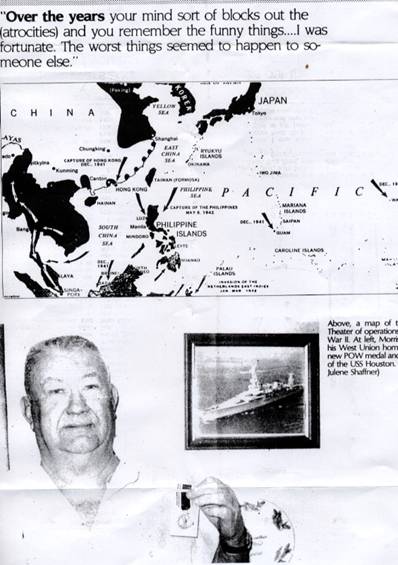

Time has softened the edges of the harsh memories leaving

behind a quiet glow of pride: pride in having served his country, pride in

simply surviving. For Edgar Morris of

Defense records indicate about 142,000 service members who were held captive in wars after April 5, 1917 are qualified for the POW Medal."It took me three and a half years (in prison) to earn this medal," said Morris, "and forty-two years to receive it. I'm proud of it."

But he quickly adds: "Don't make me out a hero. I was

just a country boy who was glad to get home."The road that led to Morris

spending time in a

during World War II began in peace time in 1939.After graduating from Mar-shall High School in 1938 Morris attended Indiana State for one year, but he says, "I didn't like school. I joined the Navy to see the world."

Morris and Don Farris of

none like the good old

The

As the Japanese made a major landing on Java in the early

hours of March 1, 1942, the

Of his Japanese captors he says, "There were good ones

and bad ones." He recalls the Korean guards in

After the war Morris' father would sponsor the English boy

in this country and eventually he would marry and raise and American family. He

still lives in

below his pre-warweight. By October 10 he weighed 160 pounds.

Morris arrived in

"We had a tough road the( first few years," he says. "1 river got our crops and it seen like we sold low and bout high."

Edgar and Mildred raised th

daughters, Betty Jo Morris West Union; Mary Ann, Mrs. Bill Crumrin

of W Union; and Marlene, now M Joe McCain of

Forty-two years have tempered his feelings for his Japanese tormentors. He admits he doesn't like see the Japanese buying up much of this country and Knows that many former serviceman are still bitter.

But says, you have to remember that their culture was different

from ours, differently.” I don't think I ever really hated them,

even back then. I was just so glad to get home.

Besides anyone who was over me

then would be an old man now."

As Memorial day approaches Morris can look back over his life and remember all who didn't come back from World War II.

He agreed to tell his story par¬tially because so many young people don't know about those days.

"I've been fortunate," he repeats.

STATEMENT OF:

RALPH EDGAR MORRIS, MUS. 2/CLASS, US NAVY, REGARDING THE SINKING OF THE USS HOUSTON, FLAGSHIP OF THE ASIATIC FLEET, AND HIS CAPTIVITY BY THE JAPANESE ARMED FORCES:

The USS Houston was in Iloilo Harbor, Philippines on December 7, 1941 when war was officially declared on Japan. The ship was used to convoy the remnants of the Asiatic Fleet through the lines of defense to their ultimate goal in the harbor of Darwin, Australia. During this trip, no enemy ships or planes caused any alarm and we had only the reports of the radio to make us realize that a war was going on. Most of our time between that period and the date of February 4, 1942 was spent patrolling and doing some convoy work. On February 4th, the Houston and other ships were attacked by Japanese bombers. This resulted in a loss of life totaling approximately 56 men.

The next encounter with the Japanese forces was on the 15th and 16th of February, when, with a convoy of American and Australian troops heading for Timor Island, we were attacked and succeeded in warding off the enemy without any loss of life on our own ship and only one killed from one of the convoyed ships. From then until about the 22nd of February, we had no actual encounters with the enemy forces but on that date, while tied up to the dock at Surabaya, Java, we had successive air raids - but no casualties.

On the 25th of February, the Houston, with as strong a task force as we could gather in those waters, set off from Surabaya to intercept an enemy convoy reported to be headed for Java. This convoy was not sighted and engaged in action until the afternoon of February 26th. The battle lasted until about midnight, about nine hours total (the Battle of the Java Sea). Most of our force was wiped out and the USS Houston, along with the Australian cruiser, HMAS Perth, steamed at full speed from the scene to the harbor of Batavia, Java, arriving on the afternoon of February 28th.

We took on fuel and were told that we had a clear run for Australia through the Sunda Straits and that the port of Perth, Australia would be our next stop. The men around my gun station were never advised as to what extent the commanders knew about our chances of making it through. We were told that no obstacle was in our way except the probability of many enemy planes being in the area, and that we would most likely have our hands full until away from the Java area.

We left Batavia Harbor on the evening of February 28th and the Perth was steaming ahead of us. At approximately 11:25 PM, in the eastern mouth of the Sunda Straits, the Perth opened fire and we all suddenly realized that we were engaging the enemy in another battle. Before many minutes elapsed, we were aware of the hopeless odds and the abandon ship call was given.

I jumped over the side and started swimming away from the ship before it went down.

After being in the water for about 11 hours, I was picked up by a pulling whaleboat from

a Japanese tanker. The Japanese had evidently rescued all of their own men that could be

found so the more humane of the remaining ships set about to rescue what numbers of us could be found. Myself and seven other Americans were taken aboard the mother ship and given proper care, including blankets, some food, drink and cigarettes. The commander of the Japanese ship asked us some questions and gave us ample opportunity to rest after our ordeal. He spoke enough English that we could make ourselves understood and the impression he gave me was that he was quite all right. However, the ship was torpedoed about two hours later and, after running the ship aground, the commander told us that he could not keep us on his ship and we would have to be transferred.

A Japanese destroyer was soon brought alongside and we were moved from the tanker to this destroyer. We were taken to the fantail of this ship and there found about 70 Australian sailors who had been aboard the Perth. On this ship, we first began to learn of the way the Japanese treated POW's. We were all gathered in one very small group and had about a 12 by 20 ft. area to stay in until they could move us to other accommodations. We remained there overnight and in the morning got a feed of a few hard biscuits and one small cup of water. We were then loaded into boats and taken to a large troopship where we were packed into a hold just below the main deck. We were given 2 pints of water and 2 pints of rice with 2 medium-sized sardines each day for a period of 9 days until we were moved onto the beach and taken by truck to our first camp (Serang Theater Prison camp, March 10, 1942 to April 15, 1942).

On April 15, 1942, we were moved to Bicycle Prison Camp in Batavia, Java. When transferred from Serang Prison Camp to Bicycle Camp, we were loaded into army trucks and rode the distance of 72 kilometers with about 30 men to each truck. The US Army would not permit any more that about 15 men to be moved more than about 2 or 3 miles in the size of truck in which we made this trip.

On October 11, 1942, we were transferred from Bicycle Camp to Changi Prison Camp in Singapore, Malaya, arriving on October 16, 1942. We were taken to Malaya by a Japanese ship, the Dai Nichi Maru. We had approximately 1,500 men in the hold where I was. Others were put into different holds and stated that they were as crowded or more so than what we were. We were given the barest amount of rations, according the standards of their (the Japanese) own rations, and allowed very little time up in the open air. Any time that a ship or small sea-going craft would approach to within four or five thousand yards, we were made to go below deck and would not even be allowed out for sanitary purposes. We were given no water except what each man could steal from the one or two decent Japanese sailors who would let a very few get water from a very questionably sanitary supply of stored water. During the trip, many cases of dysentery broke out and no consideration of sanitation was given the sick cases or to any of the rest of us except when they would condescend to let us break out on the topside to go to the latrines (which were not even adequate for one hundred men). This trip took five or six days and, at the end of that time, we were unloaded from the ship and taken by truck to Changi Prison Camp in Singapore, Malaya.

I remained at Changi until transferred to Motor Camp in Kanchinaburi, Siam (Thailand) on April 5, 1943. After leaving Singapore, we were taken first to Hampong, Siam where we were loaded into steel boxcars approximately 18 feet in length, 9 feet in breadth and 6 feet in height. Each car was made to hold 28 to 30 prisoners and travel with about half rations and no actual supply of water for a distance of about 1,500 miles. We were kept in these railroad cars continually for five days with no rests given to let us stretch or carry out the natural functions of the body. The few exceptions were stops that were made for refueling purposes and the few times we stopped to get food supplies. The food given at these points was good enough according to the standards we had been used to under the Japanese but we were also given some food that was to be carried with us for later use. Having no way to prevent it, the food was always more than half spoiled and thoroughly unwholesome. Regardless of sickness or whatever unpleasant happenings occurred on this trip, the Japanese made no allowances for this and we went on just as if we were animals.

I spent approximately eight months in Kanchinaburi Motor Camp and then was returned to Sime Road Prison Camp in Singapore. On the return trip from Siam to Singapore by rail on November 19, 1943, the situation was the same - only it was actually worse. The men had been in the jungle and working on the inhumane job of building the Siamese-Burma Railway and we were again loaded into the same size boxcars. With so many sick men this time, we were still crowded into these cars with 27 to 30 men in each one. If possible, even less consideration was given to us when it was needed, because of the great number of men, including myself, with bad cases of diarrhea, dysentery, skin sores, malaria and the many other tropical diseases contracted while working in Siam. During the return trip to Singapore, the train that I was on supposedly included the personnel that were the "fit" men of the returning group. One man that I know of on the train I was on, died of malnutrition and various diseases. To the best of my knowledge, the Japanese stopped the train at some convenient town and handed the body over to some natives who were told to dispose of it - hardly a fitting funeral for one who died for his country. On this trip, we were again on the train for a period of about five days receiving no greater amount of food than before and, as we came nearer to Singapore, the amount of food decreased. In April of 1944, I returned to Changi Prison Camp from the one at Sime Road.

I was liberated on September 7, 1945 from Changi Prison in Singapore by the American A.T.C. and was among the first of any nationality of prisoners to leave the island. Due to possible trouble with the Japanese still technically in control, we were always kept in strong groups when away from the main camp until we were finally flown away from Singapore and taken to Calcutta, India. In Calcutta, we were sent to the 142nd General Hospital that was controlled by the US Armed Forces. At the time of liberation, I weighed 100 lbs. (normal weight was 145 lbs.) and was in a very weakened condition due to recurring (bi-weekly) malarial attacks. I suffered from a lack of sufficient medical treatment and just prior to release, was almost totally blind due to malnutrition.

very little need of treatment until taken to Siam where I fell down with acute diarrhea and a very bad case of skin sores. Our own medical men described these as tropical skin scabies brought on by an insufficient amount of food and not enough variety of vitamins and calories in the small amount of food given to us. During this time, I fell off from around 140 lbs. to 113 lbs. and managed to pull through my sickness only by the moral support and kindness of some of my friends. The only treatment given by the Japanese was a liberal amount of raw charcoal for my diarrhea and a poor amount of raw sulfur mixed with a native product of palm oil (for the skin diseases). This salve was of little or no help in curing the skin trouble. Later on, in Singapore, I went almost totally blind in both eyes from malnutrition and had no actual help except from a very small amount of liquid "Marmite" (one ounce diluted with approximately ten parts of water). I also contracted malaria during the time I was kept in the hospital and was given twenty grains of quinine per day for the usual period of seven to ten days duration.

I had quite a bit of dental trouble in that I broke several teeth or corners of teeth caused by the unmerciful amount of rocks and other foreign substances in the rice issued by the Japanese for our food. I had one tooth broken off so badly that it had to be extracted practically without the use of any sedative or pain killer. The pain killer was cocaine that had been thoroughly weakened by the Japanese before being turned over to our own doctors for use on we prisoners.

The only visits that I know of into our camps by Red Cross representatives were in December — January of 194243. Later several short visits were made during the last two or three months of my captivity. Although I had no personal contact with these representatives, I am certain that some of the officers in our camp were permitted to speak with them — but only in the company of the Japanese officers. During the last visits of the Red Cross representatives, they were conducted into our camp (Changi Prison. Camp) and, under the guidance of some of the Allied officers and under the supervision of the Japanese, were permitted to make a small inspection tour into and around the camp. Their own idea of our camp was made into just a few words, "This camp is not a fit place for dumb animals to live in and surely not for about 12,000 men to be herded togethm"

I wrote approximately 30 cards or letter forms but it was not until I had been a prisoner for three years that my folks did receive one of them (January 1945) and it was the only authentic card or message from me while I was a prisoner.