![]()

![]()

USS HOUSTON CA 30

“The galloping Ghost of the

George D Stoddard

Introduction

This is Seaman 1st Class George Stoddard's story. It is also

the story of several hundred men from the U.S.S. Houston, who survived its

sinking in the flaming opening chapters of our war with

From the black days in February 1942, when the Houston

"disappeared" somewhere in the East Indies, to the day nearly a year

later, when George's grandfather received the first notice that George was

alive, his family never doubted (or stopped praying) that he would come back.

The only messages received from George during his three years as a POW were

four postcards with only the agonizingly short message, "I am well, hope

you are the same." signed George Stoddard. Those postcards meant a lot to

George's 82-year-old grandfather, George M. Stoddard, who with his wife, had

raised George from the time he was a small boy, on their ranch near

As one of the numerous cousins who flocked to "the

ranch" each summer, I can vouch for his aforementioned qualities. George

had a big, easy smile and made friends with everyone. His husky build made him

a force to be reconed with on the

Before starting George Stoddard's story, we should

understand the total picture of the Japanese offensive in the early days of

1942, and the almost hopeless position of the Asiatic Fleet, of which the

U.S.S. Houston was the backbone. February was indeed a black month for the

Allies in the Pacific. Many of our largest men-of-war still lay in shambles at

Meanwhile, the lengthening shadow of Japanese aggression was

falling on the Netherlands East Indies. One by one the lush, rich Dutch island

were falling, and a wedge of steel was being forged that pointed directly at

Java, the richest and most fabulous prize of all. Defending this prize was the

During those early days of the invasion of the Netherlands East Indies, Admiral Thomas Hart was Commander of the Asiatic Fleet (which included Dutch, English, and American men-of-war), under British General Sir Archibald Wavell. This left the Dutch without a voice in affairs most vitally concerning them. To remedy this situation, Dutch Admiral Helfrich was appointed Commander of the Asiatic Fleet and Admiral Hart "retired", supposedly because of ill health

On

The

Sinking of the USS Houston

And

Life

in Japanese Prison Camps

Life started for me at Boot Camp in

For the next two weeks, we convoyed ships and patrolled

between the

The raid lasted two-and-a-half hours, the planes making repeated bombing runs and finally leaving after making one hit on the fantail of the ship. The bomb exploded three feet above the deck killing 47 men. A nearby turret was riddled with holes, and all that was found of the Turret Officer was his shoe and part of his hand with his ring on a finger. Many other men were burned to death in the turret. One man in the stern powder room saved the ship by turning a spray valve and wetting the powder, but was so excited he wrenched the handle right off the stem.

We then proceeded under our own steam to Chilachap, on Java,

where we put 37 men ashore in a Javanese hospital, along with the wounded from

the

At Chilachap, Admiral Hart came aboard the ship and told the Captain, who later told the men, "that he didn't want our folks to accuse him of manslaughter, and there was a battle coming that was already lost before it was fought." Some of the men who realized the desperate situation we were in got together and wrote Captain Rooks (who had taken Captain Olendorf's place) a note saying, "that wherever he and the ship went, they would go too." The crew had a great deal of respect for the old man.

On the 14th and 15th of February, 1942, we were again bombed

in the harbor at

The Asiatic Fleet consisted of the Houston, a heavy cruiser;

the English light cruiser,

Early in the morning on February 27, nearly the entire fleet

went out looking for Jap ships reported to be near

45 minutes. This was the first time American main batteries had opened up on enemy ships in 25 years.

All that day and night, a running battle

took place, and at

The

After dark, half way through the Straits, we encountered the

enemy about 20 miles away. They were Jap merchant ships strung out along the

coast of

We sighted the enemy first, and battle stations were

sounded. My battle station was in the forward director just above the bridge.

The director consists of the range finders, wind velocity and direction

instruments, and the whole thing is like a big telephone booth which sticks out

over the Number 2 turret. Here we had a good view of everything that went on. I

was on the phones connected to the 5-inch anti-aircraft guns, which were aimed

at ships close in. There were eight men and one

officer in the director. Those whom I remember were: Ensign Rogers from

I'll never forget that night. It was perfectly clear and warm,

with a three-quarter moon that lighted things up, and not far away we could see

the beacons on the

A half-hour after the battle started, the

Then the Japs launched torpedo boats from their big merchant ships. One of them put a torpedo in our after engine room, cutting our speed from 32 knots down to 15. This was our second hit. Fifteen minutes later they hit us in our forward engine room, stopping us dead in the water and killing the men in both engine rooms immediately. Meanwhile, the Jap men-of-war were closing in, and some of our men on topside were killed by machine gun and shell fire. By this time, we were close enough to knock out the Jap searchlights with 50 caliber machine gun bullets, and the clatter of guns was terrific.

We were listing, and at about

From where I was in the director, at the time of the order to abandon ship, I could see Jap destroyers closing in on all sides firing shells point blank and machine gunning us. The big ships were laying back. We were lit up like a Christmas tree, the ship was listing heavily to the

Starboard side so that the water was a foot deep on the deck and the men could just barely stand without slipping down into the water. Men were cutting life rafts loose, throwing tables, mattresses--anything that would float--overboard so we would have something to climb on to. Nobody seemed scared or excited; the men were taking their time and obeying orders. All along the main deck and boat deck, men were jumping over with life rafts.

The machine gun fire was so intense, and so many men were being killed trying to get rafts over the side, that the order was given to jump without the rafts and boats. There were many dead men on the deck, and we saw one man have his head taken right off his shoulders by a 5-inch shell as he was going over the side.

Our director was jarred so much that it would barely turn, and the entrance was out over the Number 2 turret. It took us five minutes after the second order to abandon ship to get the director turned around so we could get out. All of the director crew got out safely and went to the bridge, where we joined the Captain and the quartermasters, and followed them to the radio room. We saw the Warrant Radioman trying to send messages with one arm blown off. He never got off the ship--he didn't attempt to. That man had a lot of guts. The communications officer gave each of us two or three small decoding machines to drop overboard, to prevent the Japanese from getting our code, in case the ship should go down in shallow water.

Captain Rooks was calm; he was giving orders to get as many men off as possible. By this time, the ship was listing badly. We started from the bridge down to the fo'c'sle, but as we were on the backside, decent was difficult. I was on the ladder just ahead of Captain Rooks; about halfway down, the Japs scored a direct hit on a nearby porn-porn, spraying shrapnel all over the area. One piece caught the Captain in the small of the back, and he died in his Chinese mess attendant's arms. His last words were, "Every man for himself, and may God have mercy on you." We had to force the mess attendant over the side with a .45 as he didn't want to leave the Captain.

The rest of us wanted to get down further before jumping. The ladder to the main deck was missing, so we went out on the port plane catapult. We were just starting to climb from the catapult on to the flight deck, when a shell hit a metal ammunition "ready box" near a 5-inch gun about ten feet away. A fire broke out near the "ready box" and shrapnel was sprayed through the air, killing one man near the box instantly. Shrapnel hit me in the right forearm and left elbow, but I hardly noticed it then. The fire prevented us from going any further, so we had to jump

about 60 feet to the water. I was

in a daze from the events of the past few minutes and that mad scramble, but

the water snapped me out of it. I didn't come to the surface and suddenly

realized I was still holding on to the decoding machines. I dropped them and

came right up to find myself alone. There was about two inches of oil on the

water near the ship, and I began swimming to get away before it caught fire. A

hundred yards from the ship, I ran into a Marine private, Walter Grice from

Grice and I began to swim again and, after awhile, ran into a Seaman 2nd Class named Black, who was badly wounded. There was a hole the size of a fist in his shoulder, but the salt water had stopped the bleeding. We helped him along and, about an hour and-a half after jumping, we heard the breakers roaring on the Java coast. Because of Black, we couldn't swim ashore, and the tide changed and carried us back out into the Straits again.

The morning of

We started first unloading ammunition and guns, but one of

our officers objected, so they put us to work unloading rice, fish, and other

foods. We worked steady unloading from

From

Our next stop was a well-built Javanese prison, located in

the middle of the Town of

Two days after we arrived at Serang, a Jap doctor and an orderly came outside the cells and asked if any man was injured. Some of the men had large shrapnel wounds, but the salt water had evidently kept them from festering, and even Seaman Black's shoulder wound was in pretty good shape. When my turn came, I stuck my arm with the shrapnel in it out through the cell bars and the orderly grabbed hold of it tightly. The Doc took a wire probe and, after digging for a few minutes, located the shrapnel; then, with a pair of forceps, he enlarged the wound and removed a piece of jagged metal. Man! By that time I was sweating. He poured some iodine into the wound, dressed it, and I never had any more trouble with it.

We spent the next 60 days at Serang. For reasons unknown, they took only the men under 21 and put us to work stacking bombs and rolling gasoline drums on the beach. None of the men minded working because it meant a little more to eat. Two men died of dysentery in the prison, but otherwise we stayed pretty healthy.

In the middle of April 1942, they moved us all by truck to

the Bicycle Camp in

We had to construct our own bunks or sleep on the floor. Most of the men made cots by knocking together some boards and stretching gunnysacks across them, making a pretty comfortable bed until the bed bugs got into them. Man, those bugs were big, and could they bite! Every month or two, we would clean them out by taking a lighted piece of rubber and running it along the cracks; the critters would be smoked out and burned.

A little female fox terrier that had belonged to a Dutch

Captain made its home under my bunk. All the men took a liking to her because

she hated the Japs so. The Japs had kicked her several times and one of them

had stuck her in the leg with a bayonet. Every time a Jap came near the

compound, she would bark and put us on alert. She was eating better than we

were as everyone saved a little food for her. After being with us three months,

she had 5 pups about

Twice in the four months we were at the

We had a whole arsenal buried in the garden. Forty-fives were covered with oil, wrapped up in our slickers and then buried with sweet potatoes planted over them. The Australians had two machine guns hidden in their barracks, and we were all ready to protect ourselves from the

Japs, and to be of some use in case of

Allied landings. Some of the men had a battery radio set they had stolen

out of a Jap car, so we kept up pretty well with events in the outside world.

Toward the last of September 1942, the Japs transferred us

from Bicycle Camp to the Changie prison camp near

The Technicians were sent to

We ran into one bad storm and some of the seams of the vessel were sprung, but were quickly repaired. Once the vessel rolled about 45 degrees to the starboard, and all the men in the hold slid to that side. It was a madhouse, men were piled two and three deep, and the Dutchmen, who were sure the ship was sinking, fought to get up the hatch. The ship righted and no one was hurt. The men in the hold received a tea cup of rice and some hard tack soaked in salt water three times a day. The stokers fared much better and were fed the regular ship chow.

The remainder of the trip was uneventful and we docked at

Noji, on the

By this time, most of the men were in bad shape. We all looked like a bunch of skeletons. A good many of the men were down with pneumonia, dysentery, and beriberi. Two days after we arrived, two Dutchmen who had been wasting away died of dysentery, and a few of the men began developing swollen legs from beriberi. We had to cremate the dead to prevent the further spread of disease. The Japs were getting worried that they would lose too many of us, and that the remainder would be of no use to them in the mines, so they let us rest from November 5 to January 1, 1943, and tried to fatten us up. We ate from the Jap galley and received the same food the regular miners were getting, which wasn’t very much. The men put on a little weight and most of the sick ones recovered.

In March 1943, they really put us to work, some in the iron

mines and others in a limestone quarry. I ran a pneumatic drill in the iron

mines, drilling holes for dynamite. The prisoners' shift was

from three in the afternoon to

The guards and the Commander at Kamaishi were pretty human at first. Jap army sergeants were running the camp because the Commander was in love with a neighboring Japanese girl and had his head in the clouds most of the time. One day on the parade grounds, the guards tried to make us sing some Japanese songs, but none of us would sing, which made the Japs boiling mad. The guards grabbed one Australian as he walked away and beat him up in front of the men, with their hands and a rake handle, then locked him up on half rations for five days.

After five months at Kamaishi, the regular Army guards were

replaced by older Army men who had fought in

The

In August 1943, t developed a severe, crampy pain in the

lower right side of my abdomen. The medical orderly, thinking it was

constipation, gave me a dose of salts, which promptly came up and made the pain

worse. An American doctor in the Naval Medical Corps came in and examined me,

diagnosed Appendicitis, and put me in the company hospital. The Doc had to wait

three days to operate while cat gut and instruments were sent up from a nearby

town. Then I was operated on in the finest style, with new cat gut instead of

boiled string, which was often all the medics had. Two American and two

Japanese medical orderlies helped Lt. Eppley, while a Jap doctor stood by and

watched. They gave me a spinal anesthetic and the Doc took out a large

gangrenous appendix. Later, they gave me intravenous glucose. I was a lot

luckier than men in other camps who needed surgery and had it done without

anesthetics and with a butcher knife for a scalpel. In the next couple of

weeks, I lost 16 pounds, so the

On

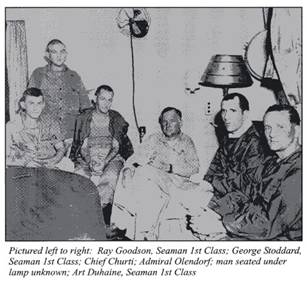

Two fellows from the Houston, Ray Goodson from

It was snowing at Yata in November, and as we had only our thin Prisoner of War uniforms and the barracks were built of very thin boards, we spent most of the time shivering. It was windy there, too, as we were so close to the ocean. After a two-day rest, we got a taste of our life for the next two years. Each day started at 5:00 a.m. by one of the Nip guards yelling, "Show", which means "Get up" in Japanese. After dressing, muster or "tinkle" is held inside the barracks. In our barracks were 35 men, all transfers from Kamaishi. The American section leader would yell Ki-oato-kay--attention--then "Bongo", which means "Count off'. We'd count off to 35 in Japanese, and woe befell the poor guy who didn't know his number; he'd get clipped in the face by a Jap guard. I was number 8. At Kamaishi, number 7 was "stitchi", but at Yata the Japs used "nana" because the word "stitchi" had something to do with their dead and its use is considered disrespectful. When we counted off that first morning, I was waiting for number 7 to sing out stitchi, but instead he said nana. I was a little slow in saying my number, so a Nip guard hit me with a stick across the side of the head.

Breakfast was served in the barracks at

The work was hard. Everything was red hot and heavy, and our day went from

A man had to do a little dealing on the black market if he didn't want to lose too much weight, because the rations issued us were not enough to keep a person alive doing the heavy work that we were doing. The Jap civilians working in the mills were worse off for clothes than we were and would trade us soy beans and rice for pieces of clothing. Everything had to be done on the quiet because if they were caught, they'd get beaten up, too. One pair of old pants would get about two pounds of beans, which were very tasty when roasted in the steel ovens and then eaten like peanuts. To get the beans back into camp, we'd put them in little bags and tie them to our legs or put them in the hollow of our backs, then walk casually past the guards, who would look only in our lunch boxes and pockets. Occasionally a good shakedown would occur, a man would get beaten up, put in the brig, and kept on half rations, but everyone had-to take those chances if he wanted to live. Those beans were worth money. A small boxful would bring a yen, or could be traded for rice and cigarettes. In all the prison camps the men who survived were those who were willing to take almost any chance to get food of any sort.

At Kamaishi, the prisoners didn't have to deal to live, but at Yata every man had to have some sort of enterprise or starve. There was a premium on bran, which tasted good and satisfied that empty feeling. Two of us were able to get some sacks of bran from a warehouse at the steel mill, which we hid in out-of-the-way places, and each day would fill little sacks to smuggle back to camp. I didn't have any trouble getting the bran into camp, but after I'd sell a cupful for half a

yen, the Nips would sometimes catch the fellow eating it and beat him up until he told from whom he had bought it. The Americans would seldom tell, but the Dutchmen's and Indians' tongues loosened easily. Practically every prisoner was involved in some kind of dealing, so it was to a man's advantage not to squeal on anybody else.

One Lieutenant was caught in a shakedown one day, after he

had bought some bran from me and was selling it to higher officers in the camp.

The Nips caught him with all of it and threatened to beat him up if he didn't

tell where he got it. He was awfully weak, sick, and scared, and a beating

would probably have killed him. My number, unfortunately, was an easy one to

remember and he gave it to them. The Nip guards immediately hauled me before

the

Next, my work record came under scrutiny and, fortunately, I was on the "Joto-ching-goto" (good worker list) for that month. The verdict was that "he would let me off lightly this time and only give me five days in the brig because of my good work record. I thought I had gotten off pretty easy, but the brig was freezing cold, as it was January and there was snow on the ground. That night I wrapped up on one thin blanket and huddled shivering in the corner until a guard took pity on me and brought another blanket and an overcoat. During my stay in the brig I received half rations and had to go to work each morning. Usually, I could find some soybeans at work and would cook them up on the back of the furnace.

When the Army Lieutenant went into the barracks that day,

the men threw shoes at him and told him to "get out; they didn't want

squealers in the barracks." I didn't hold any grudge against the man as I

knew he was sick. After we were liberated, he came up to me on

In September 1944, about 700 men captured on

The English were more susceptible to diseases and lack of food than we were, while it was the cold to which the Americans were most vulnerable. We'd been in the camp about a year when malnutrition began to take its toll. The English were hit first; most of them got "water beriberi," in which their hands and feet would swell up. One American puffed up to where he weighed 60 pounds more than usual. The Japs gave him a lot of extra fish and he recovered. Another man developed a great deal of fluid in his abdomen and chest and had to be tapped twice a week by a doctor so that he could breathe. Many fellows will be disables the rest of their lives because beriberi affected their hearts.

There were eight doctors in camp, seven Americans and one

Dutchman. Lt. Markovich was the only Navy doctor in camp. He was a very

courageous man and often went before the Jap Commandant attempting to get extra

food and drugs for the men; he was frequently slapped by the guards while

trying to get sick men excused from work. We had an Ear, Nose, and Throat and a

Bone and Joint specialist in camp, but they were hampered by lack of

instruments. Marko

Sanitary facilities were fair in camp, but at the mill they were bad, and to make matters worse, the women working in the plant used the same latrine as the Americans. At first the men were embarrassed about it, but not the Jap women,

There were a few lighter moments in camp. We were allowed three rest days a month, but had to work hard in camp that day. In the evening we'd have a concert. There was an accordion, violin and guitar in camp, given to us by the Red Cross. The men would all gather out on the road by camp at dusk, and there would be community singing--mostly old songs like "Roll Out the Barrel," and "There's a Troopship Leaving Bombay." A big heavy-set, humorous English medico named Williams, from Southmapton, would sing, dance, and put on skits, which always gave the Japs a big laugh, even if they weren't funny. There were some hot jitterbugs in camp. One of them made a blond wig out of straw with big bows on it. Somewhere he found a short silk dress and silk panties, and with some lipstick that one of his buddies had stolen from a Japanese girl's purse, he made quite a show. The men went crazy when he and his partner danced. Among the other considerable talent in camp were two Dutchmen, who were whizzes on the guitar and played and sang Dutch and Hawaiian song. After liberation they played a couple of tunes on the dock at Nagasaki, and the bandleader there to welcome us, said it was some of the best guitar playing he had ever heard. The evening entertainments were about the only thing we had to boost our morale and helped us to realize there was a better and happier life to look forward to.

During the three-and-a-half years in prison camp, we didn't receive an entire American Red Cross box. The Japs would split one box among six or seven men, keeping part for themselves, and the only packages we did receive didn't come until six months before the end of the war. I received one package and a dozen letters from home while I was there, several packages never reached me. Whenever we received a letter, the guards would stand around while we opened it and take away all the pictures. I hid some pictures of Grandpa and the family, but they found them on me in a shakedown one day, for which the guard clipped me several times and took the pictures and left them in a pile on the Commandant's porch. Later I went down and snitched them back when nobody was looking.

The Jap Sergeants in camp had the racket of opening up our packages from home. When mine came a Sergeant opened it, took out some cigarettes, candy, and socks while I stood unhappily by, but I got mad when he started to take a razor and told him he couldn't have it. He wanted me to present it to him and each time I'd refuse, he'd politely crack me on the face with the back of his hand. Finally, he let me have it after he had hit me six times.

The Jap guards were all individualists and were quickly named according to their sadistic traits. The "Water Snake" was a sly little Jap who sneaked around, spied from behind corners, and then beat the hell out of you if you even looked suspicious. The "Glove" had a white glove on his artificial hand and was known for the wicked blows he dealt out liberally with that hand. Another big Jap, with big ham-like hands who slunk along half bent over, was called the "Gorilla." One guard with some of his fingers shot off was appropriately called the "Three-Fingered Bandit," because he charged above black market prices for stolen food and goods. One poor little Jap guard we called "Liver Lip" was an exception, and was always in trouble and getting beaten up by his officers. Whenever he'd try to work a deal that the other guards would have succeeded with, we'd squeal on him and he'd get another working over.

On

It was a full year before we were bombed again, mainly

because the Americans were concentrating on the main shipping ports. On the

clear, hot morning of

One incendiary came through the roof of the mill and hit an American soldier, killing him immediately. Another piece of red hot incendiary tore off the upper part of another man's arm in the mill. He ran around looking for help, but some Japs nearby just laughed at him. He had the presence of mind to put a belt around his upper arm, which stopped the bleeding, and finally he found some Americans who laid him on a door and got him on a train back to camp, where Lt. Markovich amputated his arm.

The next three clays, the Nips were actually nice to us and

didn't push us around as much as usual, which led us to suspect the war was

over. We were sure of it when the American planes flying over the countryside

stopped strafing. Official word came from a big Jap Colonel, who lined us up

and said, "

Japanese civilians were swell to us, and a lot of Jap soldiers moving through to be demobilized didn't give us any trouble.

All the men put on a little weight that month, as every

other day a B-29 would fly over and drop parachutes loaded with food. We were

not lacking for beverages, either, as a bunch of us commandeered an electric

train (made in

A month after the end of the war, a team of Navy Corpsmen

arrived in camp to look after any wounded and get the sick out. A week later,

we boarded trains to

All the POW's from our camp went by destroyer to

We left

At dusk on