![]()

![]()

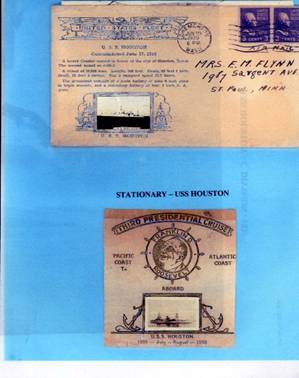

USS HOUSTON CA 30

“The galloping Ghost of the

David C. Flynn

On March 1st., 1942, I was picked up by a Japanese Whale Boat and taken to a Japanese repair ship. There were five or so other American prisoners on board. I was taken to their "sick bay", had some shrapnel removed and joined the other prisoners. We were questioned by their captain. We were fed and treated well. We knew nothing. Time elapsed (don't know how much but somewhere around a couple of hours) and the ship was torpedoed. I put my trousers on (inside out) and went over the side. At this point I was again picked up and joined Dr. Stening on the Jap destroyer. I did not met or talk to him.Topsides of the Jap destroyer was covered with prisoners - English, Australian and as far as I know one American (me). My experiences were similar to the first page of the reference letter.

I was imprisoned in the cinema in Serang, Java. We were required to sit

cross legged and my immediate associates were English. I distinctly remember

asking one of the English gentlemen what he did in civilian life. He told me he

was a "

My English friends took me to see Dr. Stening. Dr. Stening had offices (outside) and in back of the cinema not far from an open latrine. Dr. Stening removed more shrapnel using a razor blade as a scapel. Again I remember requesting something to smoke during surgery. Dr. Stening told them to give to me only after he was finished with the work at hand.

I spent the remainder of the war in bicycle camp in

A short

Autobiography – David C. Flynn

Requested by:

Shawn N. Flynn

I was born on

The

1920’s were the happiest days of my pre-teen years. The economy was good, my

dad had a prestigious job and income and this opened opportunities. Initially,

I attended the legendary one-room school. Oversized desks accommodated two

students, the first through the 8th grades were taught and German,

including German Primers, was the beginning language. Parents in the community

spoke German exclusively and relied on the school to teach their children

English. I never learned German.

The

1920’s were the happiest days of my pre-teen years. The economy was good, my

dad had a prestigious job and income and this opened opportunities. Initially,

I attended the legendary one-room school. Oversized desks accommodated two

students, the first through the 8th grades were taught and German,

including German Primers, was the beginning language. Parents in the community

spoke German exclusively and relied on the school to teach their children

English. I never learned German.

The opportunity for fame occurred early - when I was about

five or six years of age. I was selected to star (due to my unique acting

skills and the fact that I was the Athletic Coach’s kid didn’t hurt) in the

Dramatics Department’s production of The Silver King, an adaptation of William

Tell. I was William Tell’s son, David. The big

scene was the shooting of the apple off David’s head. At a prearranged signal,

the archer was to fire the arrow and David was to shake his head allowing the

apple to fall. In the confusion, the archer didn’t shoot the arrow and David

shook off the apple. This was undoubtedly the

There was one bad summer at

Page two

The Right Reverend Alcuin Deutch became Abbot and President at

The family moved to

This was the atmosphere of my teen years and I did various jobs, working in the South St. Paul Stockyards and parking cars for 20 cents an hour.

I did a stint in the Civilian Conservation Corps. (The CCC’S.) We planted trees and fought forest fires in

One summer a school buddy and I were lured to

The Flynn boys were not inclined athletically and I wanted to earn a “Letter” in the worst way. Following the summer of pitching bundles, I tried out for the Central H.S. football team. After the first day, every bone and sinew in my body ached but I stuck it out. At the season’s end (I spent it warming the bench), Central was ahead by some astronomical score and I was allowed to enter the game.

Page three

I took up boxing. My dad taught me the basics and skills

were honed at Gibbons Gym in

I went out for gymnastics, horizontal and parallel bars, horse etc. And did get a letter on the gym team.

I was a member of the Minnesota National Guard. There were

monthly drills and two weeks were spent at

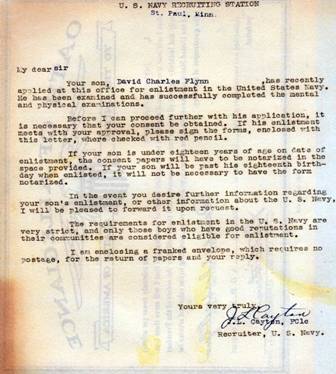

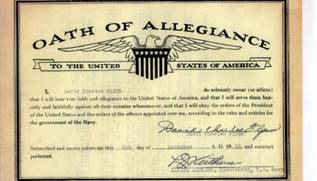

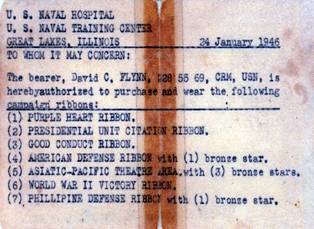

In

December of 1938 I enlisted in the U.S. Navy. The Navy attempted to groom me

for a job as a dental technician. I couldn’t stand cleaning teeth and pleaded

to be sent to sea. I got my wish and was assigned to the U.S.S. Houston.

In

December of 1938 I enlisted in the U.S. Navy. The Navy attempted to groom me

for a job as a dental technician. I couldn’t stand cleaning teeth and pleaded

to be sent to sea. I got my wish and was assigned to the U.S.S. Houston.

My first assignment was the deck force. We arose at

I was assigned as a “stricker” in the radio shack. This involved all the crumby jobs (making coffee, cleaning etc.) while learning and becoming efficient in receiving and sending data in Morse code and learning electrical theory. Mastery of practical and theoretical tests was required for advancement.

My

“General Quarters” station was as a radio operator in the plotting room. The

plotting room was located in the bottom of the ship and was considered its

“brains”. Corrections to salvos (turret firing) were made here.

My

“General Quarters” station was as a radio operator in the plotting room. The

plotting room was located in the bottom of the ship and was considered its

“brains”. Corrections to salvos (turret firing) were made here.

Page 4

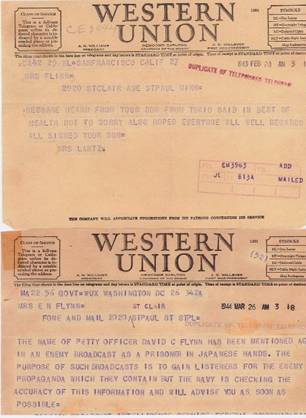

The Houston and the Australian Ship Perth were sunk in the

Battle Of The Sundra Straits on

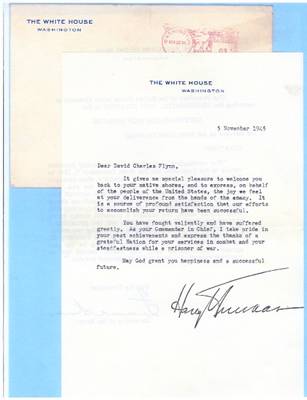

In

August/September 1945 we were liberated and taken to

In

August/September 1945 we were liberated and taken to

My reporter cousin, Joanie Flynn,

learned of my whereabouts, got me out of the hospital and together we sent for

my mother. Following a couple of weeks of dinning and Broadway Shows, my mother

and I returned to

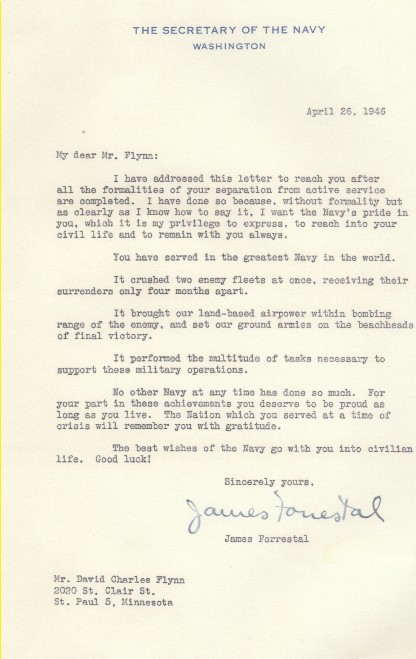

My Alma Mater, Central HS, established a college entrance

examination training program for returning GI’s. I took advantage of this and

was admitted to the U of M’s

I took a teaching job with the Warren Air Force Base in 1950

and with my wife and son moved to

In May of 1952 I went to work as an electrical engineer for

the IBM Corporation. I initially located in

I retired from IBM February 1986.

- fini -

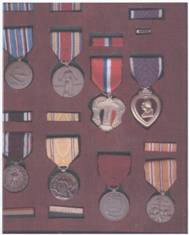

I was privileged to serve aboard the

heavy cruiser HOUSTON

By

David C. Flynn

The

USS Houston, a

The

USS Houston, a

Although not at war, strict radio silence was maintained.

Radio operators would read extensively in an effort to avoid boredom and keep

alert. I was on duty reading The Glorious Pool by Thorn Smith. The story

line was that the longer one stayed in the pool the younger one became. The main character had fallen in

the pool and was screaming at his buddy to pull him out before he passed puberty. The headphones started buzzing and I mechanically typed

the message and tossed it in the "in"

basket anxious to return to the glorious pool. A second or so later, I took another look at the message. It

simply stated: "JAPAN HAS STARTED HOSTILITIES X GOVERN YOURSELVES

ACCORDINGLY". The message was given to Captain Rooks, general quarters

were sounded and the

The next several months were spent

convoying ships in an attempt to bolster

the defenses of

The next several months were spent

convoying ships in an attempt to bolster

the defenses of

On

February 15th the

Captain

Rooks developed a technique for avoiding bombs. He'd lie on the deck and some

10 seconds after the Japanese planes released their bombs he'd order a hard

turn to port or starboard. The bombs would fall

harmlessly alongside the ship. The convoy was saved but the

Japanese had already landed on

After

seeing the convoy safely at anchor back in Port Darwin, the HOUSTON headed

North to join a fleet that was hastily being put together by

the Allies in an attempt to stop or slow down

the Japanese who were advancing southward through the South China Sea and Maccassar Straits and sweeping everything in their

path.

Under the

command of a Dutch Admiral (Doorman) the mission was doomed from its very

inception. The ships from various nations including

On

February27, 1942, the two met head on for what was to be the biggest naval battle since

Arriving at

Dutch air

patrols reported no Japanese naval activity within 250 miles. The

About

Shortly after

Some hours later, the Japanese ship was torpedoed. I went over

the side (in haste I put my pants on inside out) and started swimming. I later

found myself topside of a Japanese destroyer along with many Australian

survivors. After some time (no food or water), we were transferred to the hold

of a Japanese transport – the Sandong Maru (Japanese for safe voyage home). We were held there many days with little food

or water. (The containers that were used for human refuse also served as food

vessels.) Men continued to scream and to die.

We were taken to Serang Java. While the Japanese decided what to do

with us, we were made to stand in a destroyed railway station surrounded by

many Japanese soldiers with fixed  bayonets.

Eventually, we were herded into a native movie theater. The seats had been

removed and the prisoners seated in a cross-legged fashion. It was not possible

to lie down. The Japanese manned alcoves and boxes with machine guns. Food was

a rarity and consisted of rice and boiling water. Prisoners continued to die.

Sanitary facilities consisted of a trench located to the rear of the theater.

Flies abounded. My left leg began to swell. A couple of Aussies took me to the

bayonets.

Eventually, we were herded into a native movie theater. The seats had been

removed and the prisoners seated in a cross-legged fashion. It was not possible

to lie down. The Japanese manned alcoves and boxes with machine guns. Food was

a rarity and consisted of rice and boiling water. Prisoners continued to die.

Sanitary facilities consisted of a trench located to the rear of the theater.

Flies abounded. My left leg began to swell. A couple of Aussies took me to the  the River Quai and Death

Railway fame),

the River Quai and Death

Railway fame),  stating we'd work for Dai Nippon, would make no

attempt to escape etc. Our officers ordered us not to sign. To do so would be

considered traitorous. The officers were taken away. Every 15 minutes a

Japanese "bashing" squad would appear, yelling and would beat us with

rifle butts and clubs. It was decided between the POW's that this constituted

duress and signed their piece of paper. Life settled into a boring routine of work parties,

being sick, beatings etc. Work parties involving Aussies were always nerve

racking. One day we were required to unload 50-gallon drums of aviation fuel

from trucks. Old automobile tires were placed at the rear of the truck bed to

break the fall as drums were rolled off. After every fourth or fifth drum, an

Aussie would pull a tire away causing the drum to rupture. The leaking drum

would then be carried to a waiting barge.

Life was not completely lacking

in levity. A suyakasan (Japanese interpreter)

approached me one day. He had a letter from an American patient in a

sanatorium. The translator needed help in understanding the letter. (We never

received letters.) After lamenting his problems for a paragraph or so, the

patient went on, "say I'm sure sorry to hear of the fix you're in."

He continued, "why is a Japanese pilot like a

woman's girdle." The punch line, "a good yank can bring them both

down". "What does this mean," asked the interpreter. I tried

unsuccessfully to explain double-entendre, two meanings and play on words. He

left muttering, "wakardemasen, wakardemasen'. (I don't understand.) The Army Air Corps arrived and took the

American POW's to

stating we'd work for Dai Nippon, would make no

attempt to escape etc. Our officers ordered us not to sign. To do so would be

considered traitorous. The officers were taken away. Every 15 minutes a

Japanese "bashing" squad would appear, yelling and would beat us with

rifle butts and clubs. It was decided between the POW's that this constituted

duress and signed their piece of paper. Life settled into a boring routine of work parties,

being sick, beatings etc. Work parties involving Aussies were always nerve

racking. One day we were required to unload 50-gallon drums of aviation fuel

from trucks. Old automobile tires were placed at the rear of the truck bed to

break the fall as drums were rolled off. After every fourth or fifth drum, an

Aussie would pull a tire away causing the drum to rupture. The leaking drum

would then be carried to a waiting barge.

Life was not completely lacking

in levity. A suyakasan (Japanese interpreter)

approached me one day. He had a letter from an American patient in a

sanatorium. The translator needed help in understanding the letter. (We never

received letters.) After lamenting his problems for a paragraph or so, the

patient went on, "say I'm sure sorry to hear of the fix you're in."

He continued, "why is a Japanese pilot like a

woman's girdle." The punch line, "a good yank can bring them both

down". "What does this mean," asked the interpreter. I tried

unsuccessfully to explain double-entendre, two meanings and play on words. He

left muttering, "wakardemasen, wakardemasen'. (I don't understand.) The Army Air Corps arrived and took the

American POW's to

Survivor

from Boca tells of WWII battle that sunk Navy cruiser and his years as POW

By Luis F.

Perez

South Florida Sun-Sentinel

Posted November 30 2006

A radio operator, he had to climb seven levels using the foremast's trunk.

As he emerged three levels above the main deck, a bomb exploded nearby.

Shrapnel pierced his legs, buttocks and back. Flynn ended up in the water,

enemy fire all around.

Flynn sat in his

"The worst part was, for no reason at all, the beatings," said

Flynn, 87.

James D. Hornfischer, a writer, literary agent and former book editor,

details Flynn's story and that of survivors in a new book published Nov. 7, Ship

of Ghosts: The Story of the USS Houston, FDR's Legendary Lost Cruiser, and the

Epic Saga of Her Survivors.

Hornfischer said Flynn was the only survivor of his battle station and

his sharp memory helped the author fill in many details during interviews.

"He has almost total recall," Hornfischer said.

Flynn enlisted in the Navy as a teen in

"The Navy wanted to make a dental technician out of me," Flynn

said. "But I couldn't stand cleaning teeth."

A former ham radio operator in high school, Flynn found his way into a

job in the radio room. So he was one of the first on the ship to know that the

He was engrossed in a book when the Morse code started clicking. The

message, he said, was: "

Just three months after the attack on

The book tells the tale of the battle and more than three years the

survivors spent as slave labor for the Japanese war effort. Flynn's injuries

kept him from the railway, since his captors sent the healthy men to work, he

said.

Jack Green, public affairs officer for the

However, it had no chance against the entire Japanese naval fleet.

"The USS Houston did put up a gallant fight," Green

said. "It went down with guns blazing in an epic battle."

After the war, Flynn studied engineering, married Donna Mae, had four

sons and worked for IBM in

Flynn is the lone

That's why imperative to capture their experiences and put down on paper

their "portrait of heroism," he said.

Luis F. Perez can be reached at lfperez@sun-sentinel.com or

561-243-6641.

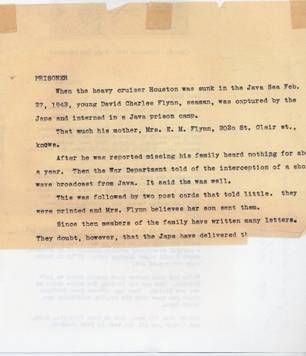

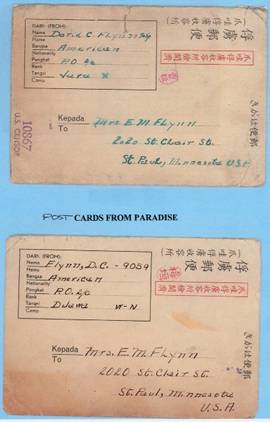

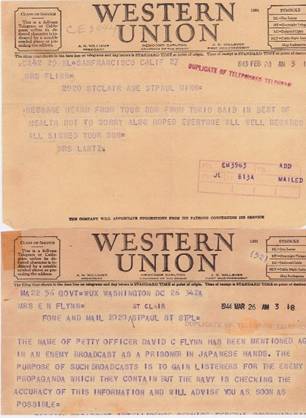

MISCELLANEOUS

The USS HOUSTON had a crew of:

1,015 officers and men

655 were killed in action, slaughtered in the water

or drowned

360 survived — of these 79 of the crew would die horrible

deaths during their 3 '/2 years as prisoners of the cruel Japanese

The City of Houston, Texas upon learning of the loss of the

$85,000,000. This was sufficient to build a second

USS HOUSTON and a small aircraft carrier -- the

An excerpt from a

tribute written by Lloyd V. Willey, U.S.M.C. and

Houston's Poet Laureate: HOUSTON, "Earned the name of `The Galloping Ghost', A fleeting shadow on the Java Coast Duty and Honor to Country, the code they knew, Well Done', to our `HOUSTON' and her crew."

NB

:

My thanks to Otto C. Schwarz for his material used in the preparation of this

talk.